WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT NOUN?

A noun is the name of a person, place, thing or idea. Whatever exists, we assume, can be named, and that named is a noun. A proper noun, which names a specific person, place, or thing (Carlos, Queen Marguerite, Middle East, Jerusalem, God), is almost always capitalized.

PURPOSE : A proper noun used as an addressed person’s name is called a noun of address. Common nouns name everything else, things that usually are not capitalized. A group of related words can act as a single noun-like entity within a sentence. A Noun Clause contains a subject and verb and can do anything that a noun can do: What he does for this town is a blessing. A Noun Phrase, frequently a noun accompanied by modifiers, is a group of related words acting as a noun: the oil depletion allowance; the abnormal, hideously enlarged nose. There is a separate section on word combinations that become Compound Noun – such as daughter-in-law, half-moon, and stick-in-the-mud.

2.1. REGULAR AND IREGULAR PLURAL NOUN

a. Song – songs → The plural of most nouns is formed by adding final –s.

b. Box – boxes → Final –es is added to nouns that end in –sh, -ch, -s, and –x.

c. Baby – babies → the plural of words that end in a consonant + -y is spelled –ies.

d. man – men ox – oxen tooth – teeth woman – women foot – feet mouse – mice child – children goose – geese louse – lice

The noun in (d) have irregular plural forms that do not end in –s.

e. echo – echoes potato – potatoes hero – heroes tomato – tomatoes

Some nouns that end in –o add –es to form the plural.

f. auto – autos photo – photos studio – studios ghetto – ghettos piano – pianos tattoo – tattoos kangaroo – kangaroos radio – radios video – videos kilo – kilos solo – solos zoo – zoos memo – memos soprano – sopranos

Some nouns that end in –o add –s to form the plural.

g. memento – mementoes/ mementos volcano – volcanoes/volcanos mosquito – mosquitoes/mosquitos zero – zeroes/zeros tornado – tornadoes/tornados some nouns that end in –o add either –es/-s form the plural (with –es being the more usual plural form).

h. calf – calves life – lives thief – thieves half – halves loaf – loaves wolf – wolves knife – knives self – selves scarf – scarves/scarfs leaf – leaves shelf – shelves

Some nouns that end in –f or –fe are changed to –ves to form the plural.

i. believe – beliefs cliff – cliffs chief – chiefs roof – roofs

Some nouns that end in –f simply add –s to form the plural.

j. One deer – two deer one series – two series One fish – two fish one sheep – two sheep One means – two means one shrimp – two shrimp One offspring – two spring one species – two species

Some nouns have the same singular and pluaral form: e.g., one deer is … two deer are …

k. criterion – criteria phenomenon – phenomena

l. cactus – cacti/cactus fungus – fungi stimulus – stimuli nucleus – nuclei syllabus – syllabi/syllabuses

m. formula – formulae vertebra – vertebrae

n. appendix – appendices/appendixes index – indices/indexes

o. analysis – analyses basis – bases crisis – crises hypothesis – hypotheses oasis – oases parenthesis – parentheses thesis – theses

p. bacterium – bacteria curriculum – curricula datum – data medium – media memorandum – memoranda

Some nouns that English has borrowed from other languages have foreign plurals.

2.2. POSSESSIVE NOUNS

Possessive nouns in a sentence communicate ownership of something, or an attribute of something or someone. Possessive nouns are words normally used as nouns, but they function as adjectives, modifying a noun or pronoun. They precede whatever it is that the possessive noun possesses. A few rules govern the form of most possessive nouns.

Possessive Singular Nouns

To form the possessive of a singular noun (a naming word that describes one person, thing or idea), add an apostrophe (‘) and an “s” to the end of that noun. For example, in the sentence, “The girl’s ball rolled into the street,” the singular noun is “girl.” To make it possessive, “girl” was changed to “girl’s.” This rule also applies to singular nouns ending in “s,” such as “class” or “Tess.” For example, “The class’s science fair project was popular,” or “Tess’s chocolate chip cookies are the best.”

Possessive Plural Nouns

Plural nouns (naming words that describe more than one person, thing or idea) usually become possessive by adding an apostrophe after the “s” at the end of the noun. To show the ball belongs to a group of girls, instead of a ball belonging to one girl, add an apostrophe after the “s” in “girls.” For example, “The girls’ ball rolled into the street. Irregular Plural Nouns Some possessive plural nouns are irregular, because the plural form of the noun does not end in “s.” Examples of irregular plural nouns are “women,” “teeth” and “children.” To form the possessive form of these plural nouns, add an apostrophe and “s” to the end of the word. For example, “The women’s baked goods were judged this morning,” “The teeth’s enamel is cracking,” and “The children’s classroom is on the first floor.”

Plural Nouns That Do Not Change Form

Occasionally, the singular and plural forms of a noun are the same, for example, fish, deer and sheep. Add an “s” or “es” to the end of the noun (whichever you would normally use to form the plural) and then an apostrophe. For example, “The fishes’ food is still floating on the surface of the water,” “The deers’ salt block is new,” and “The sheeps’ wool is ready to be sheared.”

2.3. USING NOUNS AS MODIFIERS

A noun can modify another noun by coming immediately before the noun that follows it. As a modifier, the first noun tells us a bit more about the following noun. When a noun acts as a modifier, it is in its singular form.

They do not have vegetable soup, but they do have chicken soup and tomato soup. In the sentence, the nouns vegetable, chicken and tomato are modifiers. They modify soup. Without the modifiers, we would not know what soup they have or do not have. All we would know is they have soup.

We need to use a modifying word such as an adjective or a noun, attributively (before a noun) to add to the meaning of the noun being modified. For example, we know what a ship is, but do we know what type of ship it is or what it is used for? By using a word, especially a noun acting as an adjective, before the noun ship we get to know what ship it is – a battleship, cargo ship, container ship, cruise ship, merchant ship, sailing ship, spaceship, or supply ship, or even an enemy ship or a pirate ship.

Other examples: Business/girls’/language/village school – She is a teacher in a language school. Corner/gift/pet/shoe shop – The gift shop offers a small selection of leather goods. Family/farm/pet/police/sheep/sniffer/toy dog – The police dog was sniffing round the detainee’s heels. Council/country/dream/farm/mansion/tree/summer house – They rented a council house when they got married.

More examples:

We are renovating the old farm buildings after they were gutted by fire. They spent the weekends doing the vegetable garden. She kept her money box under her bed. A car bomb went off, injuring a dozen people.He lay in the hospital bed reading a library book.

When a noun used as a modifier is combined with a number expression, the noun is singular and a hyphen is used, as follow:

They built their own half-timbered house overlooking the river. He does a one-man show in a open-air theatre. / His one-man business is expanding fast. The pilot overshot the runway and crashed his two-seater aircraft.The three-day horse-riding event will take place next week. They lived in a four-bedroom house in the suburbs. She plays in a five-girl rock band. He will have to serve a six-year sentence for burglaries. He got a seven-month contract to work on an offshore oilrig. The historic eight-room mansion stands in 60 acres of parkland. The 100-year-old mansion stands in 60 acres of parkland.

2.4. COUNT AND NON-COUNT NOUNS

Nouns can be classified further as count nouns, which name anything that can be counted (four books, two continents, few dishes, a dozen buildings); mass nouns (or non-count nouns), which name something that can’t be counted (water, air, energy, blood); and collective nouns, which can take a singular form but are composed of more than one individual person or items (jury, team, class, committee, herd). We should note that some words can be either a count noun or a non-count noun depending on how they’re being used in a sentence:

a. He got into trouble. (non-count)

b. He had many troubles. (countable)

c. Experience (non-count) is the best teacher.

d. We had many exciting experiences (countable) in college.

Whether these words are count or non-count will determine whether they can be used with articles and determiners or not. (We would not write “He got into the troubles, “ but we could write about “The troubles of Ireland.” Some texts will include the category of abstract nouns, by which we mean the kind of word that is not tangible, such as warmth, justice, grief, and peace. Abstract nouns are sometimes troublesome for non-native writers because they can appear with determiners or without: “Peace settled over the countryside.” “The skirmish disrupted the peace that had settled over the countryside.” See the section on plurals for additional help with collective nouns, words that can be singular or plural, depending on context.

Other Example:

After two months of rainstorms, Fred carries his umbrella everywhere in anticipation of more bad weather.

Rainstorms = count noun; weather = noncount noun.

Because Big Toe Joe has ripped all four chairs with his claws, Diane wants to buy new furniture and find the cat another home.

Chairs = count noun; furniture = noncount noun.

When Mrs. Russell postponed the date of the research paper, smiles lit up the faces of her students, filling the room with happiness.

Smiles = count noun; happiness = noncount noun.

Because the beautiful Josephine will help Pablo with his calculus assignments, he never minds the homework from Dr. Ribley’s class.

Assignments = count noun; homework = noncount noun.

Know the different categories of noncount nouns. The chart below illustrates the different types of noncount nouns. Remember that these categories include other nouns that are count. For example, lightning, a natural event [one of the categories], is noncount, but hurricane, a different natural event, is a count noun. When you don’t know what type of noun you have, consult a dictionary that provides such information.

Category Examples

Abstractions advice, courage, enjoyment, fun, help, honesty, information, intelligence, knowledge, patience, etc.Activities chess, homework, housework, music, reading, singing, sleeping, soccer, tennis, work, etc. Food beef, bread, butter, fish, macaroni, meat, popcorn, pork, poultry, toast, etc. Gases air, exhaust, helium, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, pollution, smog, smoke, steam, etc. Groups of Similar Items baggage, clothing, furniture, hardware, luggage, equipment, mail, money, software, vocabulary, etc. Liquids blood, coffee, gasoline, milk, oil, soup, syrup, tea, water, wine, etc. Natural Events electricity, gravity, heat, humidity, moonlight, rain, snow, sunshine, thunder, weather, etc. Materials aluminum, asphalt, chalk, cloth, concrete, cotton, glue, lumber, wood, wool, etc. Particles or Grains corn, dirt, dust, flour, hair, pepper, rice, salt, sugar, wheat, etc.

Know how to indicate number with noncount nouns. Thunder, a noncount noun, cannot have an s added at the end. You can, however, lie awake in bed counting the number of times you hear thunder boom during a storm. When you want to indicate number with a noncount word, you have two options. First, you can put of in front of the noncount word—for example, of thunder—and then attach the resulting prepositional phrase to an appropriate count word.

Kristina heard seven claps of thunder. A second option is to make the noncount noun an adjective that you place before a count noun. Then you could write a sentence like this: Thunderheads filled the sky.

Here are some more examples:

Noncount Noun Countable Version

advice pieces of advice

homework homework assignments

bread loave of bread, slices of bread

smoke puffs of smoke, plumes of smoke

software software applications

wine bottles of wine, glasses of wine

snow snow storms, snowflakes, snow drifts

cloth bolts of cloth, yards of cloth

dirt piles of dirt, truckloads of dirt

Understand that some nouns are both noncount and count.

Sometimes a word that means one thing as a noncount noun has a slightly different meaning if it also has a countable version. Remember, then, that the classifications count and noncount are not absolute. Time is a good example. When you use this word to mean the unceasing flow of experience that includes past, present, and future, with no distinct beginning or end, then time is a noncount noun. Read this example: Time dragged as Simon sat through yet another boring chick flick with his girlfriend Roseanne.

Time = noncount because it has no specific beginning and, for poor Simon, no foreseeable end.

When time refers to a specific experience which starts at a certain moment and ends after a number of countable units [minutes, hours, days, etc.], then the noun is count. Here is an example:

On his last to Disney World, Joe rode Space Mountain twenty-seven times. Times = count because a ride on Space Mountain is a measurable unit of experience, one that you can clock with a stopwatch.

Form of Nouns Nouns

can be in the subjective, possessive, and objective case. The word case defines the role of the noun in the sentence. Is it a subject, an object, or does it show possession?

- The English professor (subject) is tall.

- He chose the English professor (object)

- The English professor’s (possessive) car is green.

Nouns in the subject and object role are identical in form; nouns that show the possessive, however, take a different form. Usually an apostrophe is added followed by the letters (except for plurals, which take the plural “-s” ending first, and then add the apostrophe). See the section on possessives for help with possessive forms. There is also a table outlining the cases of nouns and pronouns. Almost all nouns change form when they become plural, usually with the simple addition of an –s or –es. Unfortunately, it’s not always that easy, and a separate section on plurals offers advice on the formation of plural noun forms.

Assaying for Nouns*

Back in the gold rush days, every little town in the American Old West had an assayer’s office, a place where wild-eyed prospectors could take their bags of ore for official testing, to make sure the shiny stuff they’d found was the real thing, not “fool’s gold.” We offer here some assay tests for nouns. There are two kinds of tests: formal and functional – what a word looks like (the endings it takes) and how a word behaves in a sentence.

Does the word contain a noun- making morpheme? Organization, misconception, weirdness, statehood, government, democracy, philistinism, realtor, tenacity, violinist.

Can the word take a plural-making morpheme? Pencils, boxes

Can the word take a possessive-making morpheme? Today’s, boy’s

Without modifiers, can the word directly follow an article and create a grammatical unit (subject, object, etc.)? the state, an apple, a crate

Can it fill the slot in the following sentence: “(The) ______ seem(s) all right.” (or substitute other predicates such as unacceptable, short, dark, depending on the word’s meaning)?

VERB

Verbs carry the idea of being or action in the sentence.

- I am a student.

- The students passed all their courses.

As we will see on this page, verbs are

classified in many ways. First, some verbs require an object to complete their meaning:

“She gave _____ ?” Gave what? She gave money to the church. These verbs are called transitive. Verbs that are intransitive do not require objects: “The building collapsed.” In

English, you cannot tell the difference between a transitive and intransitive verb by its form; you have to see how the verb is functioning within the sentence. In fact, a verb can be both transitive and intransitive:

“The monster collapsed the building by sitting on it.”

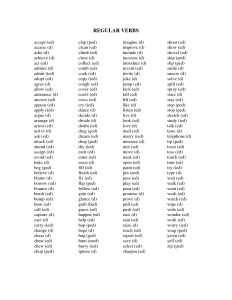

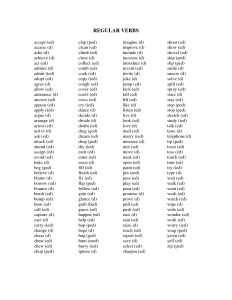

List of Regular and Irregular Verb

ADJECTIVE

Adjectives are words that describe or

modify another person or thing in the

sentence. The Articles — a, an, and the — are adjectives.

- the tall professor

- the lugubrious lieutenant

- a solid commitment

- a month’s pay

- a six-year-old child

- the unhappiest, richest man

If a group of words containing a subject and verb acts as an adjective, it is called an Adjective Clause. My sister, who is much older than I am , is an engineer. If an adjective

clause is stripped of its subject and verb, the resulting modifier becomes an Adjective Phrase : He is the man who is keeping my family in the poorhouse.

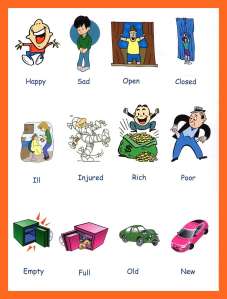

Degrees of Adjectives

Adjectives can express degrees of

modification:

Gladys is a rich woman, but Josie is richer than Gladys, and Sadie is the richest woman in town.

The degrees of comparison are known as the positive, the comparative, and the superlative. (Actually, only the comparative and superlative show degrees.) We use the comparative for

comparing two things and the superlative for comparing three or more things. Notice that the

word than frequently accompanies the

comparative and the word the precedes the superlative. The inflected suffixes -er and -est suffice to form most comparatives and superlatives, although we need -ier and -iest

when a two-syllable adjective ends in y (happier and happiest); otherwise we use more and most when an adjective has more than one syllable.

ADVERB

Adverbs are words that modify a verb (He drove slowly .

— How did he drive?) an adjective (He drove a very fast car.

— How fast was his car?) another adverb (She moved quite slowly down the aisle.

— How slowly did she move?)

As we will see, adverbs often tell when, where, why, or under what conditions something happens or happened. Adverbs frequently end in -ly ; however, many words and phrases not ending in -ly serve an

adverbial function and an -ly ending is not a guarantee that a word is an adverb. The words lovely, lonely, motherly, friendly, neighborly, for instance, are adjectives:

That lovely woman lives in a friendly

neighborhood.

If a group of words containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb (modifying the verb of a sentence), it is called an Adverb Clause :

When this class is over , we’re going to the movies.

When a group of words not containing a

subject and verb acts as an adverb, it is called an adverbial phrase . Prepositional phrases frequently have adverbial functions (telling

place and time, modifying the verb):

He went to the movies .

She works on holidays.

They lived in Canada during the war.

And Infinitive phrases can act as adverbs (usually telling why):

She hurried to the mainland to see her

brother.

The senator ran to catch the bus.

But there are other kinds of adverbial

phrases:

He calls his mother as often as possible .

Kinds of Adverbs

She moved slowly and spoke quietly .

She has lived on the island all her life.

She still lives there now.

She takes the boat to the mainland every day.

She often goes by herself.

She tries to get back before dark .

It’s starting to get dark now .

She finished her tea first.

She left early .

She drives her boat slowly to avoid hitting the

rocks .

She shops in several stores to get the best buys.

References

Azar, Betty Schrampfer.1999. Understanding and Using English Grammar 3rd Edition. Pearson Education, Inc. New York.

http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/adverbs.htm